When teachers are trusted, students thrive

/Guest contributor Adriana Mata is an anchor teacher for Discovery Class 1 at The Compass School in Austin, Texas, where she works with early elementary students in small group settings. With over a decade of classroom experience across diverse learning environments, she is also pursuing doctoral work with a focus on writing and Chicana feminisms. Her teaching emphasizes place-based learning, cultural pedagogy, and student agency.

Some of the most important moments in learning happen when a teacher has the time and trust to truly notice a child. In many schools, public and independent alike, educators carry the weight of systems they didn't shape. Mandates, pacing pressures, and test-driven priorities push teaching craft to the margins, leaving teachers to apply their deepest skills last. When that happens, students feel it first.

But what changes when teachers aren't constrained?

I've seen what becomes possible when educators are trusted as curious, thoughtful professionals whose voices meaningfully shape how learning unfolds:

When time constraints are replaced with intention.

When the preset curriculum gives way to student interest.

When testing is reframed as coaching.

What emerges is a learning environment where children are deeply known, and where rigor comes from attention rather than pressure.

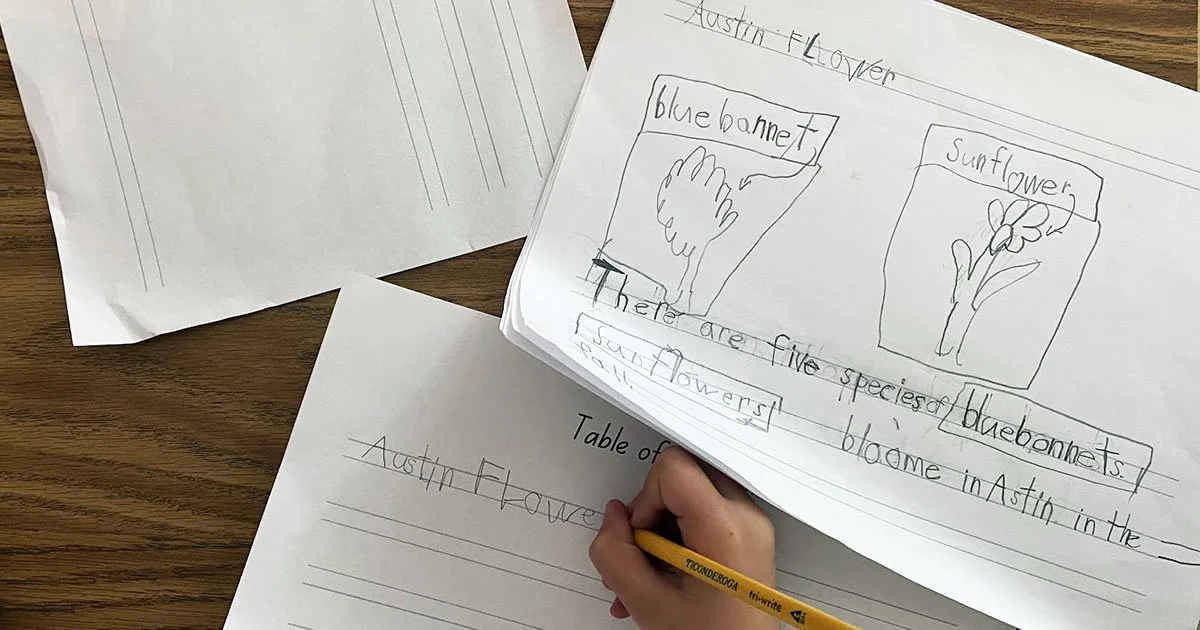

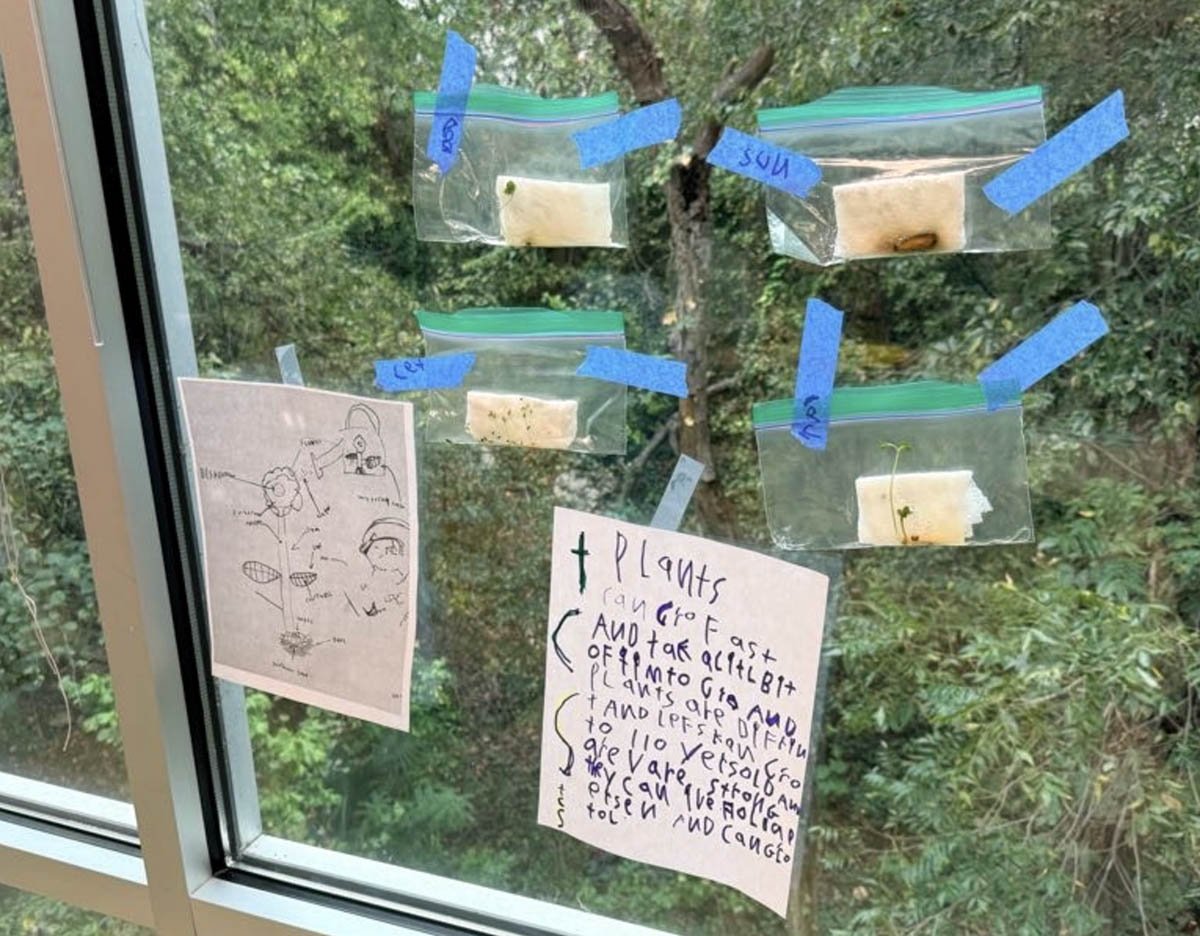

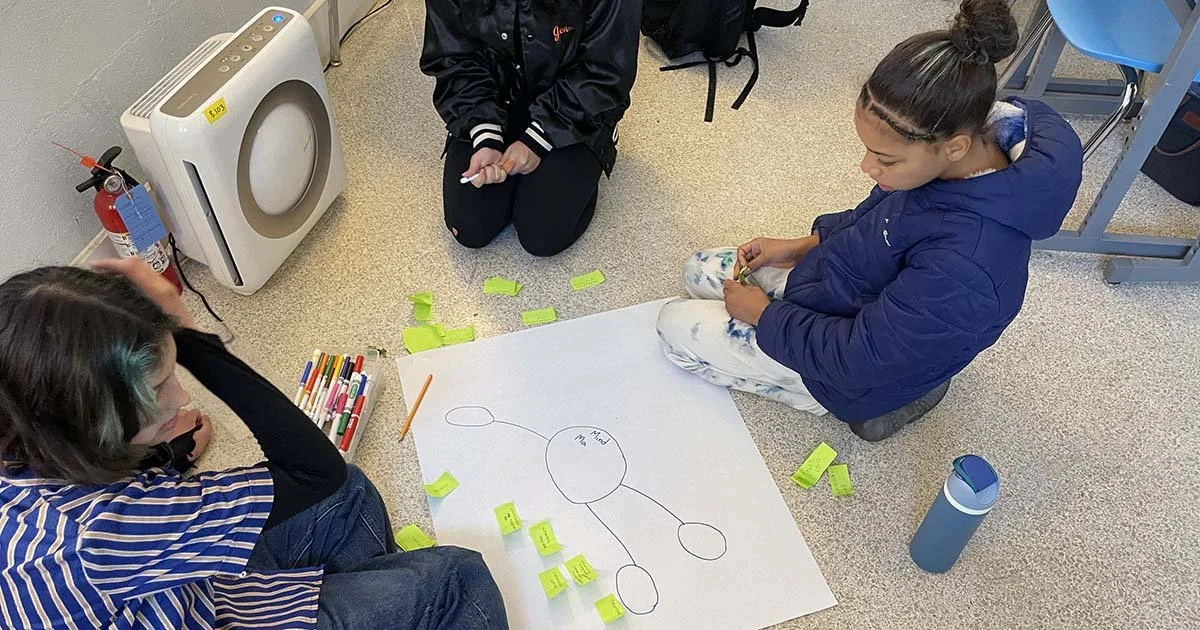

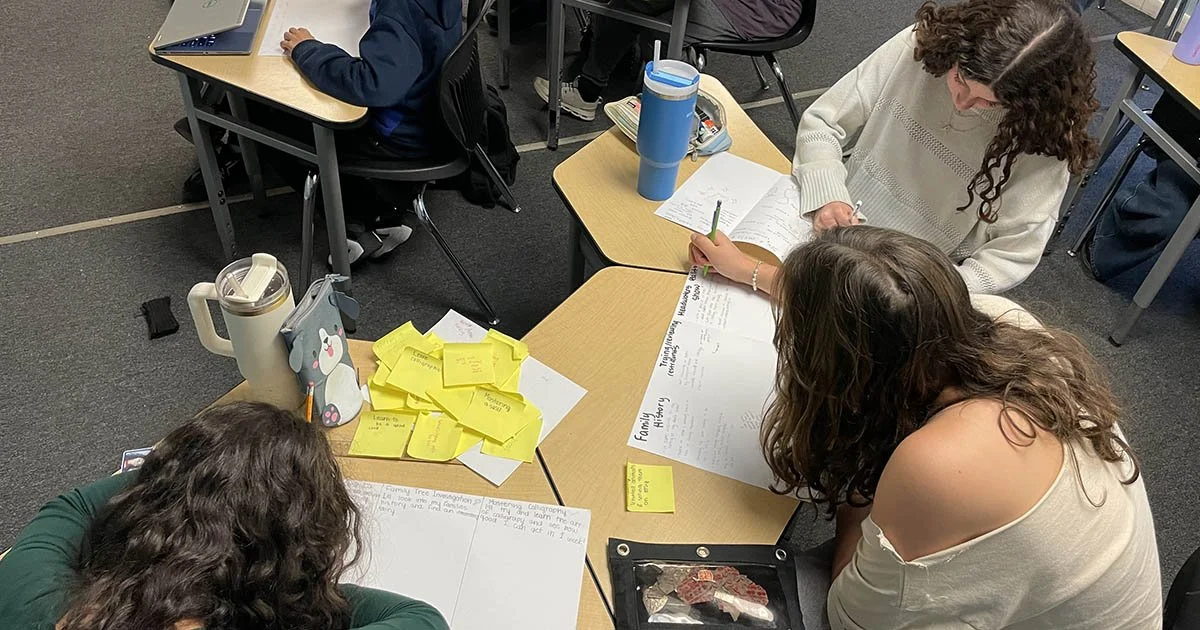

Recently, I worked with a student who shared that they didn't have any particular interests and felt unsure about beginning a deep dive project. Instead of rushing past that moment, we slowed down. Through observation and conversation, a quiet curiosity emerged: plants. From there, I guided, encouraged, and challenged the student to research, document, question, and present their learning. What began as uncertainty became ownership. This is what student-driven learning can look like, not the absence of structure, but the presence of responsive, skilled guidance grounded in professional judgment.

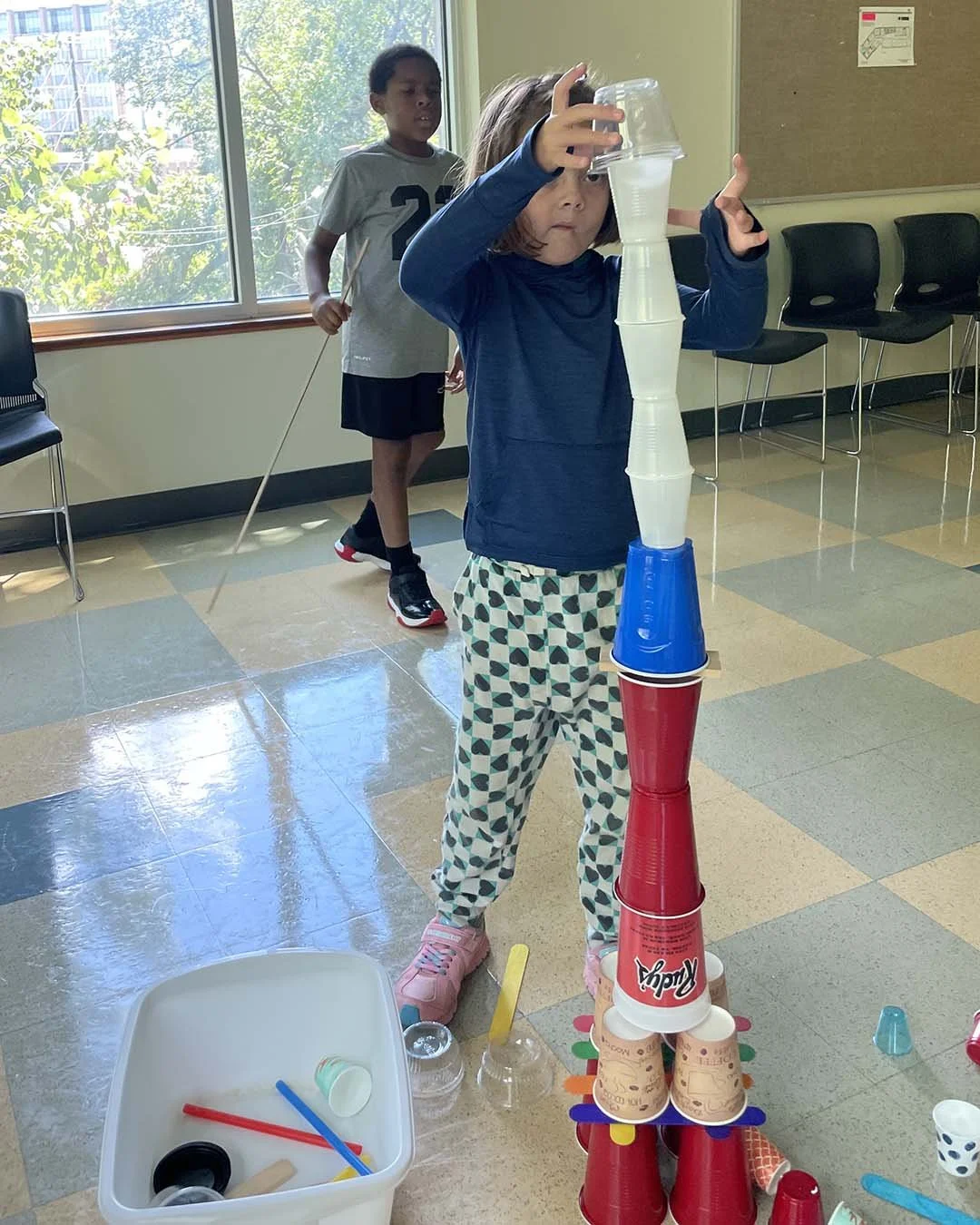

When teachers have autonomy, families see the impact in their children's academic growth, but also in their confidence, agency, and willingness to take intellectual risks. Students learn to articulate their thinking, revise their work, and see themselves as capable learners. This growth is not accidental; it is the result of the teacher's voice being central to daily decisions about learning.

For educators who sense they're capable of more than constraint-driven systems allow, this recognition matters. Ecosystems that trust teachers are rare. They work because trust is operational, not aspirational. When educators are given both the tools and the autonomy to practice their craft fully, students benefit directly from that alignment.

Education should be thoughtful, human, and deeply responsive to who children are and who they are becoming. When educators are trusted as professionals, and when students are invited to discover, develop, and lead their own learning, schools become places where children and the adults who teach them are trusted to grow.

—Adriana Mata | The Compass School