Answering the “Should I?” and “Can I?” questions

/Ken Hawthorn founded and runs “a school in a makerspace”: Austin School for the Driven. For this guest post I invited Ken to share his decision-making process when students propose projects that could be dangerous or controversial. In his candid response below, he invites readers to help him think through two specific (and real) dilemmas, either by emailing him directly or by leaving a comment here on the blog. —Teri

Our school bifurcates the teaching of skills and ethics. The answer to almost any “Can I?” question at our school is “Yes, and here is how.” The answer to “Should I?” needs to be explored in parallel with the “Can I?” question. As a school founder, I take great pride in how far we are willing to take that bifurcation at Austin School for the Driven.

Recently I have been navigating a few topics where I find myself hesitating to live up to giving students all the knowledge so they have the power to take a responsible approach to decision making in our school. With so many unique schools keeping Austin weird, I hope sharing my own challenges and discomforts around some student questions may be helpful or thought-provoking to others.

Student Question #1: Can we spray-paint under the bridge and make a mural?

I have been navigating this question for a year now. Spray-painting in the hands of children is nothing new at Austin School for the Driven. We have used spray paint on our RC car bodies and water-dipping projects. It makes me smile every time our school takes a field trip to Home Depot and we get the stink eye from security as our kids fill a small cart with spray paint cans. What is new is the student request to spray-paint in a public place.

RC car bodies spray-painted by students at Austin School for the Driven

There is existing spray paint on the walls of the tunnel they are targeting. If I said yes to this question, I would be a teacher leading students on an urban beautification project. On the other hand, saying yes to this question could be seen as an adult leading minors to commit a crime. For me this is a difficult question.

The students are absolutely serious about the quality of the proposed mural. To date, the students have scanned the tunnel with Lidar and created a 3D digital model that we can deploy at full-size scale as augmented reality inside of our classroom. We have found a spray paint simulator and are learning about the variety of nozzles that can be used to get very narrow or wide paint patterns.

What is the right decision here? What side should the “Should I?” land on this question?

Lidar scan used by Driven students to create a 3D model of a local tunnel showing preexisting graffiti

Student Question #2: How does vaping work?

This is a “Can I?” question. I am totally fine having students do research and then discussing the “Should I?” part. What is less comfortable for me is providing knowledge involved with the “Can I?” question. It is sad that this question came up on one of our hikes along Shoal Creek Trail because there were so many of the disposable vaping devices littered along the trail.

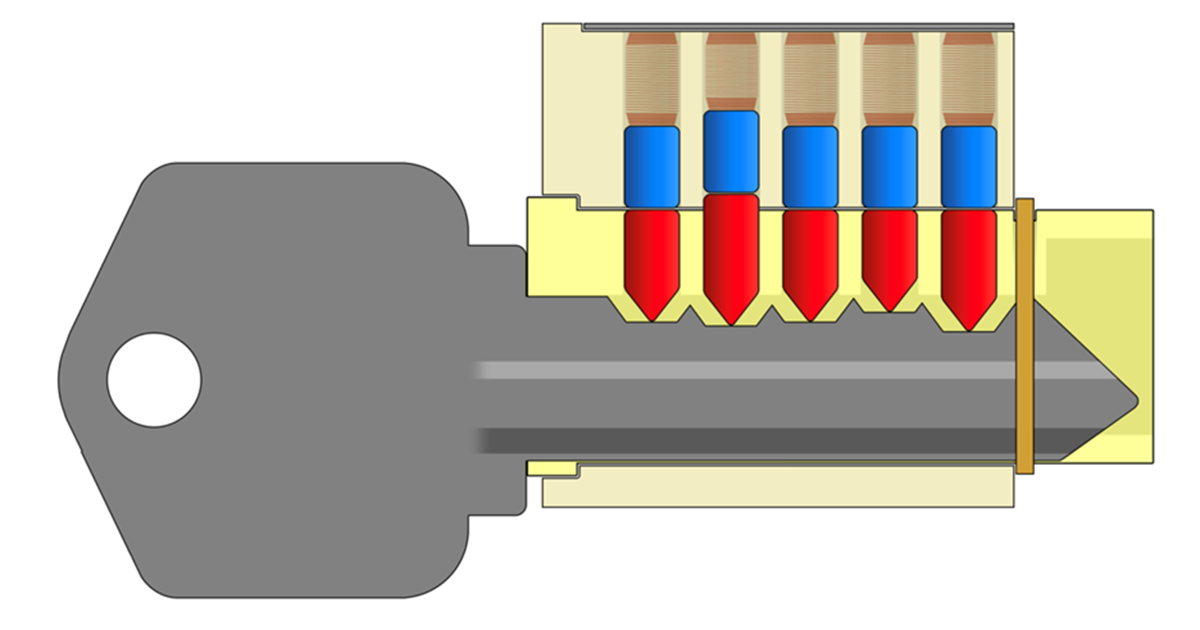

No, we are not bringing a vaping device to campus, but building a functional model to vaporize propylene glycol or glycerol could be really educational. A vaping device actually is a reasonably technical machine. You have the battery, the heating coil, the baffle mesh, and a computer to regulate voltage, measure resistance, and target a certain wattage. There is a charging circuit and another circuit that acts as a fail-safe if the temperature goes up or there is too much battery discharge. There are also thousands of other machines we could build in the lab. Would building a model in some way still glamorize vaping?

I ask this question, and the question about spray-painting the bridge, because I don’t yet have an answer; I do not know what the right answer is. Austin School for the Driven exists as an experiment to see what happens when we hold standards and at the same time maximize student agency within a framework of “Yes,” “No,” and “Maybe” answers to questions of “Can I” and “Should I,” which then define the learning boundaries of the school.

Kenneth Hawthorn | Austin School for the Driven