What is critical thinking?

/

Guest contributor Stephanie Simoes is the founder of Critikid.com, a website dedicated to teaching critical thinking to kids and teens through interactive courses, worksheets, and lesson plans.

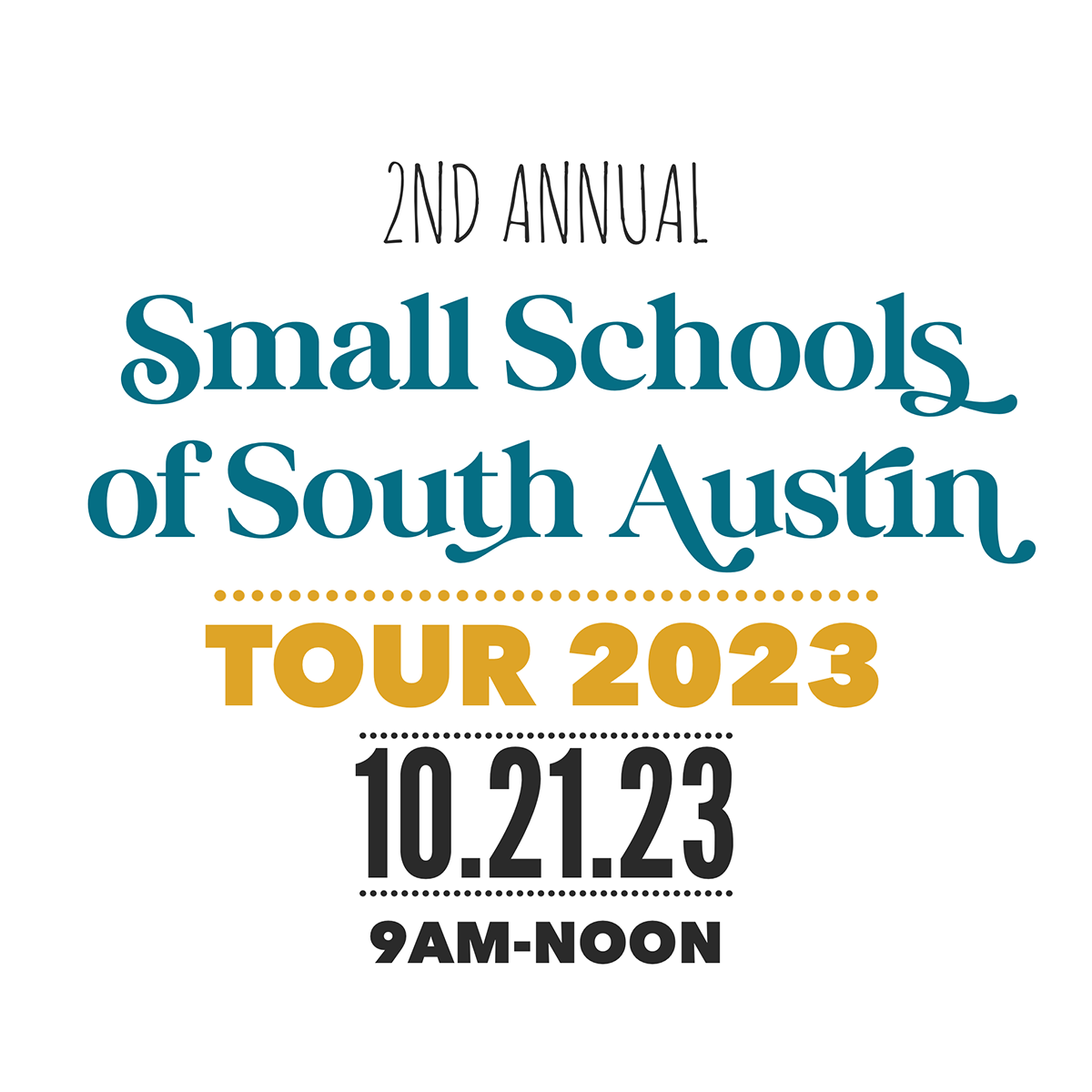

“Critical thinking” is a trendy term these days, especially in the education world. Alternative schools in Austin commonly advertise that they encourage kids to think critically. Conversations about critical thinking are often accompanied by some version of the Margaret Mead quote, “Children must be taught how to think, not what to think.” But such discussions often neglect a crucial question: “What does it mean to teach children how to think?” Critical thinking is an abstract term. Are we all on the same page when talking about it?

As the founder of a critical thinking site for kids, this question is important to my work. We all get what “thinking” is, so the real question is—what makes it “critical”? I like to use a simple definition: critical thinking is careful thinking. It requires slowing down and questioning our assumptions.

Fast and Slow Thinking

Our brains are hardwired to respond to stimuli quickly, a crucial advantage in emergencies. When faced with a potential threat, immediate reaction is essential—there’s no time for deliberation. While this quick thinking might make us mistakenly perceive a harmless situation as dangerous, it’s a safer bet to err on the side of caution in high-stakes moments. It’s a matter of survival: better to assume danger where there is none than to overlook a real threat.

While fast thinking[1] is a valuable skill, it is prone to errors.

Here’s an example. Try to answer this question in less than 5 seconds:

If 1 widget machine can produce a total of 1 widget in 1 minute, how many minutes would it take 100 widget machines to produce 100 widgets?

After you’ve given your quick, intuitive answer, take as much time as you need to think about it.

Many people’s initial, intuitive response is 100 minutes. However, with more careful thought, we see that the correct answer is 1 minute. (The production rate per machine is 1 widget per minute. The rate doesn’t change with the number of machines.)

The key takeaway of this puzzle is that careful, deliberate thinking is often more accurate than quick thinking.

Applying slow, careful thinking to every daily decision would be impractical. Imagine how long you would spend at the grocery store if you conducted a deep analysis of every single choice! In many cases, our intuitive, fast thinking serves us well. However, problems can arise when we cling to the conclusions drawn by our fast thinking—especially in situations where accuracy matters.

In the widget machine problem, it’s relatively straightforward to recognize and correct our intuitive response with a bit of careful thought. However, letting go of our intuitive conclusions is not always this easy.

Humility and Critical Thinking

We might cling to our intuitive answers, even when faced with clear evidence or reasoning that challenges them, for several reasons.

First, it can be hard to change our minds when the intuitive answer feels very obvious or the correct answer is very counterintuitive. A famous example is the Monty Hall Problem. The correct answer to this puzzle is so counterintuitive that when Marilyn Vos Savant published the solution in Parade Magazine in 1990, the magazine received around 10,000 letters (many from highly educated people) saying she was incorrect!

It can also be challenging to let go of wrong answers when we have invested in them, such as by spending time and energy defending them. Sometimes, it’s simply a matter of not wanting to admit we were wrong.

Critical thinking requires more than just slow, deliberate thought. It also demands an open mind, humility, and an awareness of our minds’ flaws and limitations.

Building Blocks of Critical Thinking

Paired with slow, deliberate thought and humility, the following tools help us to be better critical thinkers so we can communicate more clearly—even when communicating with ourselves:

An understanding of cognitive biases: These are systematic errors in our thinking that can lead us astray. There are many online resources that explore these biases in detail.

An understanding of logical fallacies: These are flawed arguments. Logical fallacies can be used deliberately to “win” a debate, but they’re often made accidentally. Recognizing logical fallacies helps us to keep conversations on track. You can learn about some common logical fallacies in my Logical Fallacy Handbook or teach your kids about them with my online course, Fallacy Detectors.

Science literacy: We were taught many facts in science class, but many of us never really learned what science is and how it works. This is the foundation of science literacy. For an introduction to this, I recommend biology professor Melanie Trecek-King’s outstanding article “Science: what it is, how it works, and why it matters.” Another important part of science literacy is knowing How to Spot Pseudoscience.

Data literacy: Data literacy is the ability to properly interpret data to draw meaningful conclusions from it (and to know when drawing certain conclusions is premature). It means understanding how data is collected, identifying potential biases in data sets, and understanding statistics. Data literacy helps us make sense of the vast amount of information we encounter daily. You can introduce your teens to some common errors in data collection and analysis in Critikid’s course A Statistical Odyssey—a course that adults have enjoyed and learned from, too!

Preparing Kids for the Misinformation Age

A quick scroll through social media reveals a minefield of bad arguments and misinformation. You have probably come across logical fallacies like these:

“You either support A or B.” (False dilemma)

“Buy our product—it’s all natural!” (Appeal to nature)

The lack of science literacy among influential voices is also concerning. I can’t count how many times I have seen or heard the phrase,

“Evolution is just a theory.”

This phrase confounds the scientific and colloquial definitions of theory. If unintentional, it demonstrates a lack of science literacy; if intentional, this is a logical fallacy known as “equivocation,” in which a word is used in an ambiguous way to confuse or mislead the listener.

The need for data literacy is also apparent. You may have heard arguments like:

“Illness X has increased since Y was introduced, so Y must be the cause.” (Mistaking correlation for causation)

“There are fewer cases of food poisoning among people who drink raw milk than those who drink pasteurized milk.” (Base rate neglect)

We have an incredible amount of data at our fingertips, but without data literacy, we don’t have the proper tools to make sense of it all.

Critical thinking shouldn’t be taught as an afterthought; it needs dedicated, explicit instruction. Children face a battlefield of misinformation and faulty logic every time they go online. Critical thinking is their armor. Let’s help them forge it.

Stephanie Simoes | Critikid.com

[1] Nobel-prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls fast thinking “system 1 thinking” in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. I highly recommend this book to anyone who finds the content of this blog post interesting.