Project Week at Headwaters School: Turning curiosity into creation

/Paul Lambert, Headwaters School mathematics guide

Like Paige Arnell’s recent guest post for the blog, this piece by Paul Lambert is about one school’s approach to creativity—in this case a step-by-step collaborative method to get special student projects underway. Paul is a mathematics guide at Headwaters School in Austin, Texas.

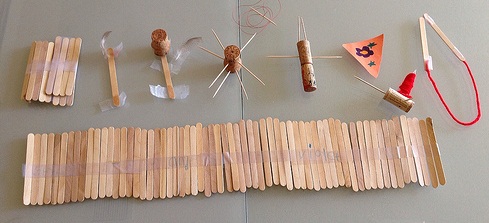

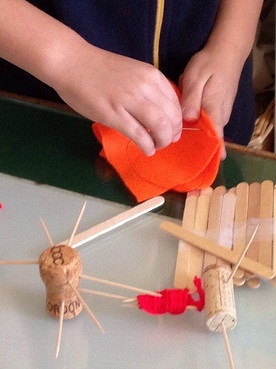

Every year since 2004, Headwaters School has held Project Week, a unique departure from regular classes during which students choose their topic of study, determine their learning objectives, and share their passions with our school community. Over the years, Project Week has inspired a variety of creative projects, including building a robotic wolf, writing and illustrating a children’s book, designing a biometric sensor, and producing a short documentary about Project Week itself.

Embarking on a big creative endeavor like this can feel overwhelming for our students, so for the last two years we have instituted a structured, step-by-step idea-generation process tailored for middle and early high school students. This framework allows every student to transform their curiosity into a fully realized creation.

Step 1: Brainstorming

We start by getting students' creativity flowing. Each student spends five uninterrupted minutes writing their interests, curiosities, or things they’d like to explore on sticky notes—one idea per note. To encourage a productive session, we emphasize three practices:

Deferring judgment: Every idea is valid at this stage of the process.

Encouraging wild ideas: Unconventional concepts often lead to breakthroughs.

Prioritizing quantity: More ideas mean more possibilities.

By the end of this stage, students have a stack of sticky notes brimming with potential.

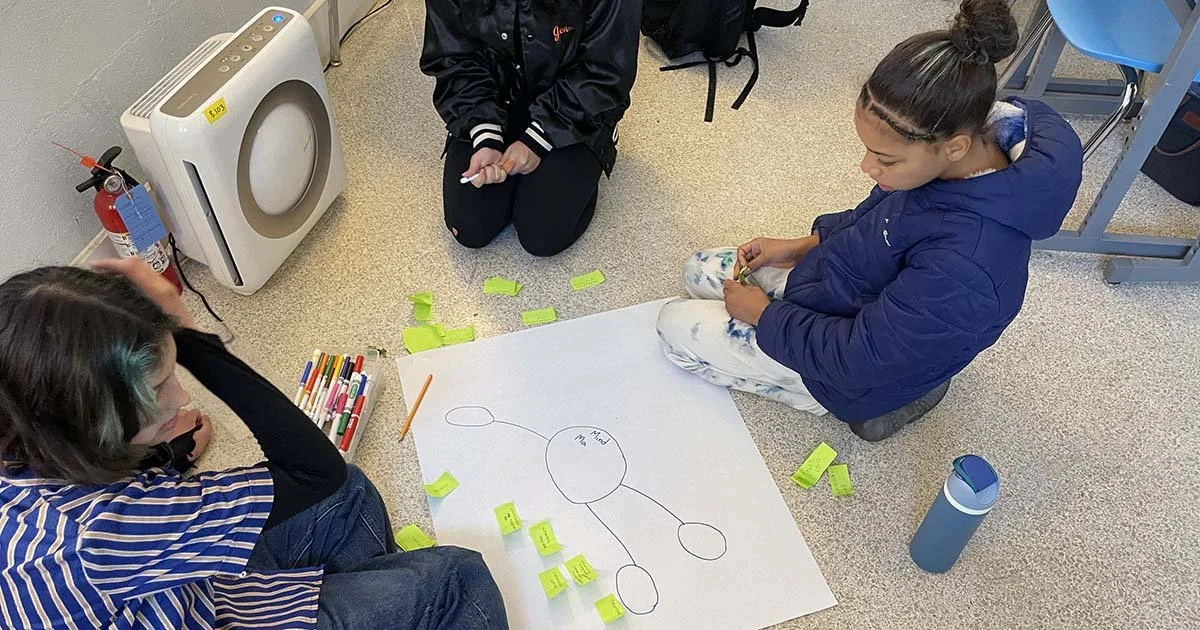

Step 2: Mind-Mapping

Next, students work in groups of three or four to organize their sticky notes into categories. Each group decides how to categorize ideas and how each idea fits inside the category. Then, they create a mind map with “Project Week” at the center and their categories branching out as spokes. This collaborative activity helps identify connections and themes, setting the stage for focused exploration.

Headwaters students mind-mapping

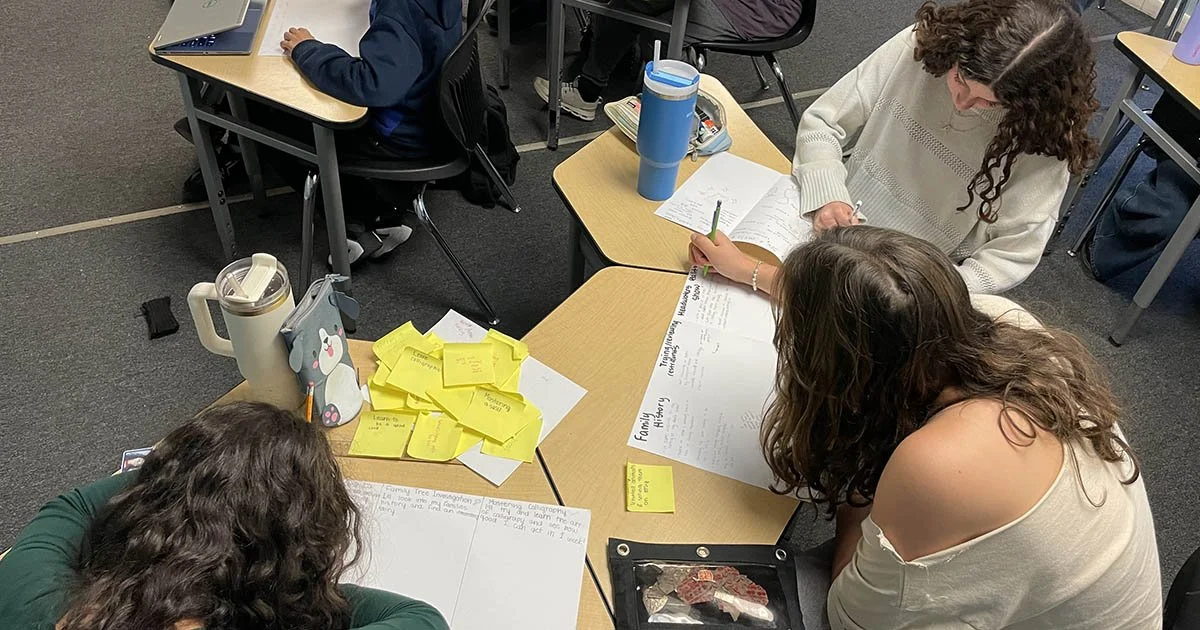

Step 3: Concept Development

Once students have collected and categorized their interests, they dive into developing some full project concepts. Students are encouraged to think about how they could combine multiple interests (from the same category or across categories) into one project idea. This is a process that takes time and a great deal of careful consideration.

Each student divides an 11" x 17" sheet of paper into three sections and is given 15 minutes to develop three distinct project ideas with as much detail as possible.

The papers are then passed to the next member of the group. Each student has 3 minutes to add to or modify the concepts on this page, ensuring no one erases anything.

Papers are passed around the group until all members have added to each paper.

This method encourages diverse perspectives while preserving the originality of each idea.

Concept development in a Headwaters classroom

Step 4: Gallery Walk

To gather broader feedback, we have a Gallery Walk. Students display their concept pages around the room or on their desks, and their peers provide constructive comments and suggestions as they stroll around the space. To foster a supportive environment, we ask students to offer two positive remarks for every critique.

By the end of this stage, each concept is enriched with fresh insights, helping students refine their ideas further.

Step 5: Finalizing the Project Idea

With these improved ideas, students choose one concept to develop into their final Project Week plan over the next week. They reflect on key questions to guide their decision:

What do you hope to learn?

What skills do you hope to develop?

What do you hope to create?

Why is this project important to you?

Why is this project interesting to you?

Answering these questions helps students articulate the purpose and significance of their project, preparing them to pitch their ideas the following week.

Why This Process Works

This idea-generation process was adapted from the Engineer Your World course at the University of Texas and designed with our middle and high school students in mind. It breaks the intimidating task of starting a project into manageable, engaging steps while fostering creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking. By the time students present their project pitches, they’ve already invested thought, effort, and enthusiasm into their ideas while also receiving feedback, lowering the risk when presenting.

A Headwaters sixth-grade passion project on female artists

Through brainstorming, mind mapping, developing their concepts, and peer feedback, students learn how to turn a simple curiosity into a meaningful project—and, in the process, discover the joy of exploring their passions.

—Paul Lambert, Mathematics Guide | Headwaters School