Why should I take an art class? I don’t want to be an artist when I grow up!

/

Alison Pilon Nokes teaches art, among other subjects, at Huntington-Surrey High School in Austin. Her guest contribution here is adapted from her recent post on the school’s own blog.

After about ten years in the visual art education world, I feel pretty strongly that everyone should take an art class—every year, if possible!

Throughout my own educational and professional experiences, I have always felt freed by the opportunity for creative problem solving and exploration of visual media provided through the visual arts. I was, and still am, able to process many different parts of my life through an art outlet. And while I do, personally, as an adult, identify as an artist, I think the benefits of working through an artistic process—much like the experience of working with the scientific method in a science course—are worthwhile for everyone to experience as they venture through their education, no matter what they end up doing and becoming.

We are living in a rapidly changing world. In many ways, we cannot even imagine what the work force and daily life are going to look like for our kids when they come of age. This year of rapid adjustment to virtual learning and social distancing has certainly given us all a taste of how flexible we need to be and how quickly our world can change. What we do know is that students who can think critically and creatively about a variety of complex problems are going to have the best chance for success in just about any setting.

Not every student who is taking an art class is planning to apply to art school for college. In fact, most aren’t (just as not every student who is taking a biology course plans to become a biologist). It is with that in mind that I design lessons and projects for my art students. My lessons provide students with opportunities to play with materials they may not have used before, discover for themselves how those materials work, and consider how they can use them to meet their needs. My lessons present students with a problem, a dilemma, or an obstacle and ask them to come up with an out-of-the-box solution.

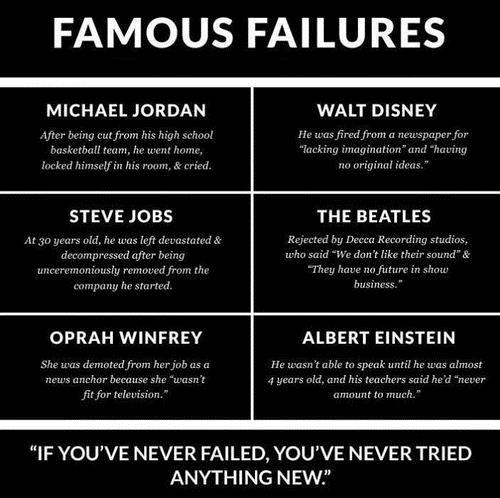

As much fun as it is for families and friends to walk into a student art show at the end of the year full of beautiful finished work, the reality of art is that most often what students make is messy and strange. For every finished work of art that is “pretty,” there are often several unsuccessful attempts (I’m purposely avoiding the term “failures”). Those unsuccessful attempts—those messy and strange drawings, paintings, and sculptures—are what show the important lessons of art: the processes of working out a solution to a problem. As a teacher of art, the most important thing to me is not what the final product looks like. Rather, I want my art students to put forth their best effort, maintain a good attitude about trying, and work through the hard process of solving problems in innovative ways with materials that may be new to them.

Alison Pilon Nokes