A place at the table for failure

/Educational psychologist Breana Sylvester, PhD, is leading her family on a journey through the alternative education landscape, observing and chronicling for others what she learns about noncoercive, interest-based learning communities. Here she shares an essay on failure adapted from her own blog, Dandelion Adventures.

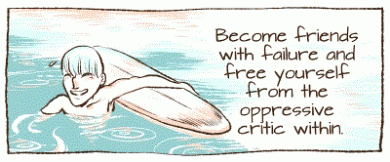

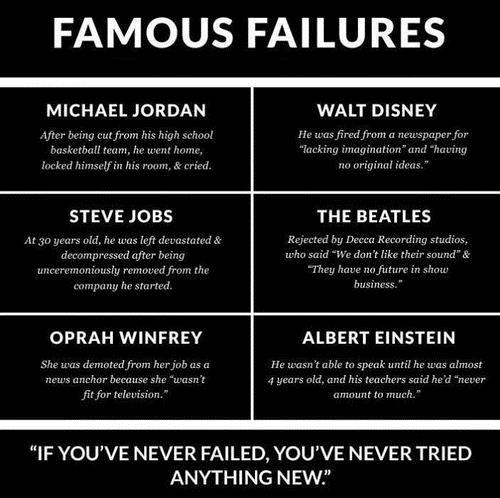

Recently Ashton Kutcher made a surprise appearance at TEDYouth and decided to talk not about his successes but rather about his failures. Since then my corner of the internet has been atwitter with people sharing fun ideas, and I have seen a terrific number of illustrations of the utility and beauty of failure. Here’s an anonymous one currently making the rounds on social media:

What an incredibly important message to give to learners, child and adult! Failure is an opportunity to learn and grow. Sometimes it also helps us choose direction. Rarely will failure ruin all our plans for the future; usually it tells us we need to find new ways to approach our goals, and sometimes it even gives us hints as to how. In fact, not allowing children to fail can be impairing.

Yet our culture attaches a great deal of shame to failure. What do we lose, though, if failure is not an option? How does fear of failure influence how we treat one another and ourselves?

The above comic triggered some connections that I would like to share from what I have learned from educational psychology. In particular, Goal Orientation Theory and self-compassion came to mind.

Goal Orientation Theory, also known as Achievement Goal Theory, posits that our reasons for working toward goals can vary greatly and that our orientations toward our goals have implications for how well we learn new things and how we deal with failure in the process of learning. When we learn things because we enjoy the process of learning, we are more likely to remember what we learned and also more likely to see failure as a natural part of the learning process. This is known as adopting a mastery orientation.

Another orientation posited in earlier work on goals was called performance orientation, wherein the learner’s motivation behind work toward a goal was primarily that of success at that goal, whether it be making a good grade or obtaining recognition (or avoiding failure). It is possible to have a mix of more than one orientation toward a goal. Psychologists have done a great deal of research on these goal orientations and over time have modified the theories. (You can find updated information and research findings here.)

It seems clear to me that high pressure to succeed in the form of high-stakes assessments and competition for recognition such as we find in most, if not all, traditional school settings could only contribute to the performance orientation. I find myself wondering, then, what would a learning environment that supports a mastery orientation look like? What if failure and success weren’t so dichotomized?

The second concept that sprang to mind was that of self-compassion. I used to teach a college course on applied learning and motivation theory, and we would talk about inner voice and its influence on motivation. When we got to the part about the influences of our inner voice on our motivation and emotion, students would tell me how cheesy the idea of positive self-talk seemed to them. So at the beginning of the next class I would ask them to write down what they would say to a friend who was failing two classes and was afraid of losing his financial aid at the end of the semester. Once they were done, I’d ask them to turn over the card and write what they would say to themselves in the same situation. It wasn’t uncommon to hear nervous giggling and even gasps at the realization that their words to themselves were far harsher, and frequently unhelpful.

I was fortunate in my graduate school experience to learn a good bit about the psychological concepts of mindfulness and self-compassion from Kristin Neff, an expert on the study of the latter as a psychological construct. Of course, both mindfulness and compassion are appropriated from Buddhist philosophical concepts, but there is a lot of promising research on how they are currently being used in counseling settings.

It’s true that we rarely afford ourselves the same understanding, patience, and acceptance in our failures as we do those we care about; it takes practice and even hard work to learn to see failure as a necessary part of the human condition, but by freeing ourselves from the judgment of failure, we can more clearly see the path forward and enjoy the journey!

An Example: My own fear of failure

Recently Jerry Mintz, director of the Alternative Education Resource Organization (AERO), asked me what my goals were in regard to our family’s adventure in learning about alternatives to traditional educational settings. Up to that point, I’d felt that I had a somewhat clear idea of the things I knew I wanted to learn and those that I could pick up along the way. Even so, his question initially felt scrutinizing, given the early stage of our adventure planning. On reflection I realized that the reason the question made me feel uncomfortable was that I am afraid of failing, afraid of letting down the people who devote their lives to the learning environments I am just beginning to explore.

Just the tiniest shift in mindset—allowing myself to acknowledge my fear of failure and approaching his question as a learning opportunity—led me to experience a much deeper and more thought-out conceptualization of our adventures, which will, in all probability help me convey my goals to those I hope to work with. Yes, there’s a chance I may still fail at my ultimate goal of encouraging a large number of people to think more critically about how we educate students and teachers, but once my fears have been acknowledged, I can see past them, and I can see that what we gain by trying will be an experience of great value for me, for my family, and hopefully for others!

Here’s wishing you all wonderful opportunities to face your fears!

Breana Sylvester